Protesters attend a “Me Too” rally to denounce sexual harassment and assaults of women in Los Angeles, California, on November 12, 2017. (Photo: Ronen Tivony / NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Oldspeak: “The powerful men who’ve been outed for harassment, assault and other abuses are not going to prison, for the most part — and even if they did, would they become less harmful? Punishment-based approaches to social harms are the default in our society, but they have consistently availed us nothing. Few rapists ever see the inside of a jail cell, whereas 86 percent of women who have spent time in jail are survivors of sexual violence. Marginalized women face continued criminalization for acting in their own defense, and across the board, US prisoners face alarming rates of sexual violence while confined. But in this supposed watershed moment, high-profile white women, whose voices have been loudly amplified, have offered little critique of the carceral and punitive approaches that have only added additional layers of abuse and exploitation to an already violent society…

Are we creating an environment where survivors are more supported? Has the average, working-class survivor been given new tools with which to halt their abuse? What about survivors living in the margins, whose cries are often unheard, even when they have disclosed? And will this fleeting moment, of simply naming and condemning “predators,” bring neglected survivors closer to the care and resources they need? Will it transform the people who harmed them? I think not….

So, what is this cultural moment accomplishing? For one thing, it is feeding a conflation that will ultimately be weaponized against the marginalized. I know no one wants to hear it, but let’s challenge ourselves to take a look backward, at the history of criminalization and punishment. There have been other historical moments when a lewd comment or gesture (or the perception or accusation of such) evoked the same rage and response as an all-out assault. Throughout US history, in the eyes of the law and white society, Black and Brown men and boys have been viewed as potential predators. Historically, those who have been deemed “predators” have been ensnared by social mechanisms that were supposedly geared toward “public safety.” If you’re thinking, “the men who are being brought down now are white and powerful, so these situations aren’t comparable,” I would ask you to consider what happens when the high-profile white women who’ve taken the wheel, in this social moment, get out of the car and move on to other things. That car will still be in motion, but who will be driving? And who will they run down?….

Treating people who commit sexual violence as outliers, who can simply be ejected from our society, will not unravel the norms, policies and practices that make sexual violence inevitable in this society. Pretending we can effectively address the problem with a smattering of takedowns will actually reinforce those norms, policies and practices.” –Kelly Hayes

“Yeeeesssss…. Brilliant, contextualized and nuanced analysis of the current media frenzy around harasser shaming. Focusing attention on well known personalities doesn’t allow for the deep critical analysis necessary to truly deal with root causes of behavioral patterns grounded in patriarchal systems of racial and gender based oppression and domination that have been in place for eons. Will we change how we rear our male youth? Will we stop imbuing them with madness like “boys don’t cry”, “be aggressive” “be competitive”, “dominate the competition”, “don’t be a pussy”, “you (insert insulted behaviour here) like a girl”? Will we stop condoning violence when “justified”? Telling them feelings, emotions, compassion & empathy are only for girls? Will we stop teaching them to exploit others weaknesses? We see this violence, abuse and exploitation replicated in how we treat other species and our Great Mother Earth. Is there any wonder that violence, abuse and oppression of women is the norm here? A pervasive, global phenomenon in this barbaric culture of cruelty? These conditions will not change with more punishment & condemnation of “predators”. These conditions will not change due to virtue signaling women’s marches, rallies & protests. Actual change will require root level rethinking of how we raise men. It will require deprogramming and decolonizing of minds and ways of being. How we define manhood. Of the behaviors reinforced and condoned by men. A global renunciation of pathological patriarchy. Short of that sadly we can expect more of the same, ad infinitum.” –Jevon

Written By Kelly Hayes @ Truthout:

Ten years before Alyssa Milano turned #MeToo into a viral hashtag, the concept was created by Tarana Burke, a Black grassroots organizer, as a means to help survivors, particularly survivors of color, get the support they need. Recently, the hashtag quickly galvanized a post-Weinstein movement to expose men whose harassment and assault had gone either unseen or unacknowledged. As the hashtag gained popularity, Burke acknowledged feeling “a sense of dread,” because “something that was part of my life’s work was going to be co-opted and taken from me and used for a purpose that I hadn’t originally intended.” But within days, Burke had been credited for the concept, and granted some amount of attention, which for many, was enough to silence concerns about whether the moment reflected Burke’s crucial purpose — to help and support survivors.

Punishment-based approaches to social harms are the default in our society, but they have consistently availed us nothing.

“What the Me Too campaign really does, and what Tarana Burke has really enabled us to do, is put the focus back on the victims,” Milano said in an interview with Robin Roberts.

But has the evolution of this cultural moment, as Milano claims, actually put the focus on victims? In recent weeks, I have seen a steady stream of allegations, but what I have not noticed is a larger public conversation about how to materially and emotionally support victims. I have seen no increase in advocacy for programs that help survivors access resources. Conversations about prevention are usually reduced to catchphrases about “teaching your sons not to rape” — a process that has no established road map in a culture of rape. And then there are the takedowns, which are treated as ends in themselves, as though robbing some powerful men of some of the trappings of fame materially alters the landscape of sexual violence.

Somehow, in the hands of powerful white women like Milano, a moment of solidarity and a discussion of how we can support survivors became a large-scale mission to take “these men” down. So, they’re being brought down. Now what?

The powerful men who’ve been outed for harassment, assault and other abuses are not going to prison, for the most part — and even if they did, would they become less harmful? Punishment-based approaches to social harms are the default in our society, but they have consistently availed us nothing. Few rapists ever see the inside of a jail cell, whereas 86 percent of women who have spent time in jail are survivors of sexual violence. Marginalized women face continued criminalization for acting in their own defense, and across the board, US prisoners face alarming rates of sexual violence while confined. But in this supposed watershed moment, high-profile white women, whose voices have been loudly amplified, have offered little critique of the carceral and punitive approaches that have only added additional layers of abuse and exploitation to an already violent society.

Will this fleeting moment, of simply naming and condemning “predators,” bring neglected survivors closer to the care and resources they need?

It is possible that renewed interest in rape survivor Cyntoia Brown’s case could mark the beginning of a larger public dialogue about the criminalization of survivors. But given Cyntoia’s extraordinary circumstances — including the fact that she was trafficked as a child and has pursued higher education while incarcerated — it seems more likely that her case will be approached as an anomaly, rather than one that exposes a system that grinds survivors under. Meanwhile, the emphasis of the vast majority of public conversations remains on the allegations and the perpetrators, not on supporting survivors.

I will admit, I was here for the takedowns, for a moment. I am not sorry rapists and those who have harassed are losing their jobs or the respect of their peers. What I am worried about is what we are building right now, and what we are not building.

Are we creating an environment where survivors are more supported? Has the average, working-class survivor been given new tools with which to halt their abuse? What about survivors living in the margins, whose cries are often unheard, even when they have disclosed? And will this fleeting moment, of simply naming and condemning “predators,” bring neglected survivors closer to the care and resources they need? Will it transform the people who harmed them? I think not.

As a Native person, I am acutely aware of sexual violence, and the ways in which it is invisibilized. Fifty-six percent of Native women have experienced sexual violence — which means Native women are 2.5 times as likely to experience sexual violence as any other group. I do not expect that the current flurry of celebrity takedowns will have much impact on the violence Native people experience, or even spur a greater awareness of that violence, or the transformative efforts to overcome it.

So, what is this cultural moment accomplishing? For one thing, it is feeding a conflation that will ultimately be weaponized against the marginalized. I know no one wants to hear it, but let’s challenge ourselves to take a look backward, at the history of criminalization and punishment. There have been other historical moments when a lewd comment or gesture (or the perception or accusation of such) evoked the same rage and response as an all-out assault. Throughout US history, in the eyes of the law and white society, Black and Brown men and boys have been viewed as potential predators. Historically, those who have been deemed “predators” have been ensnared by social mechanisms that were supposedly geared toward “public safety.” If you’re thinking, “the men who are being brought down now are white and powerful, so these situations aren’t comparable,” I would ask you to consider what happens when the high-profile white women who’ve taken the wheel, in this social moment, get out of the car and move on to other things. That car will still be in motion, but who will be driving? And who will they run down?

We already know.

When we demand total disposal of “bad” people as a social standard, we are creating a social mechanism. When we put serial rapists in the same category as people who say, or once said, terrible things, we are creating a social mechanism. When we foster that conflation, and call everyone it encompasses “predator,” we are creating a social mechanism. When we demand the disposal of all such “predators,” we are creating a social mechanism. Sometimes, those mechanisms are enacted at a personal level; sometimes, they are codified, like the “three strikes” laws Hillary Clinton pushed forward by vilifying Black children.

Personally, I am working to root the word “predator” out of my vocabulary because we aren’t hunting for predators in an otherwise pristine forest. The forest itself is on fire.

When everyone who broke a law, any law, became a “criminal,” a social mechanism was born.

When Black children became “super predators,” a social mechanism was born — one that fed Black children to the prison industrial complex.

When conflations and generalizations that render people disposable are loosed upon the world, I worry about where they will land, because, on a long enough timeline, they will always land in the same places.

Personally, I am working to root the word “predator” out of my vocabulary. I always knew it was a term that dehumanized, but some harms would provoke me to spit out a word I knew was harmful and ugly. However, in the current climate of conflation, the word “predator” could mean anything, and therefore means nothing. It’s not a meaningful characterization. It’s a garbage chute into which people are being tossed.

If you’re thinking, “Well, these men are garbage,” I would counter that if that’s the case, we are still swimming in trash, and merely celebrating the removal of a few Hefty bags.

As much as we would like to “other” harassers and abusers — marking them as separate from ourselves — “predators” are human beings, as are your friends and family members, and many of you, who have at times crossed lines and broken boundaries. I believe that many such people can transform their harms. My first concern, however, is to support the healing of survivors, which is what I thought I was doing when I wrote my #MeToo post. In truth, that’s what #MeToo still means to me, because the need for us to find each other and heal and love, and our ability to transform the world that hurt us — that’s all still there when we are ready to do the harder work.

People like Tarana Burke were doing that difficult work long before this viral moment, and will continue to do so long after it has passed.

Treating people who commit sexual violence as outliers, who can simply be ejected from our society, will not unravel the norms, policies and practices that make sexual violence inevitable in this society. Pretending we can effectively address the problem with a smattering of takedowns will actually reinforce those norms, policies and practices.

We aren’t hunting for predators in an otherwise pristine forest. The forest itself is on fire. It always has been. And when the predator hunt ends, we’ll still be standing in the flames.

=========================================================================

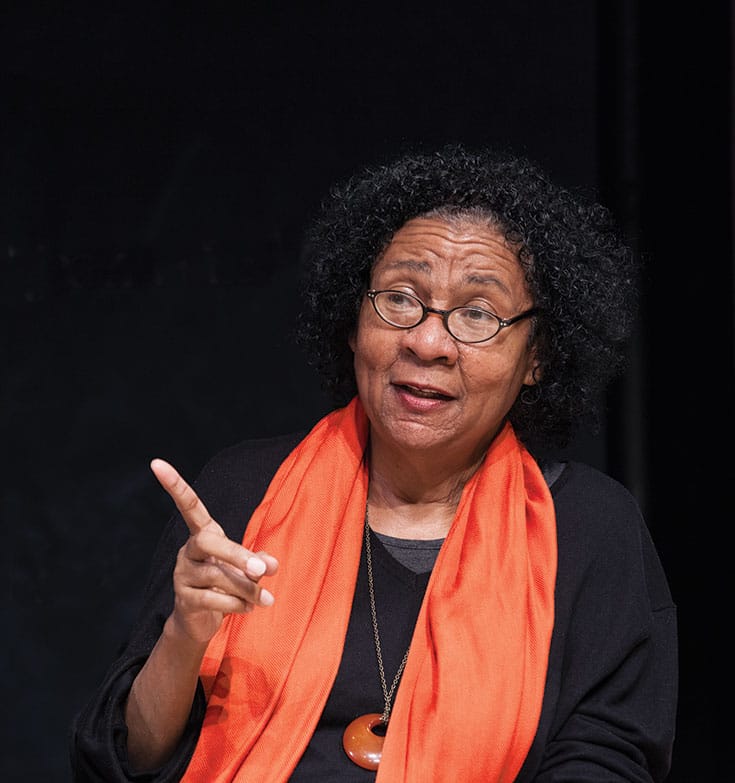

Kelly Hayes

Kelly Hayes is Truthout’s social media strategist, as well as a contributing writer. She is also a direct action trainer and a cofounder of The Chicago Light Brigade and the direct action collective Lifted Voices. Kelly’s contribution to Truthout’s anthology Who Do You Serve, Who Do You Protect? stems from her work as an organizer and her ongoing analysis of movements in the United States. Her work can also be found on her blog, Transformative Spaces, in Yes! Magazine, BGD and the BGD anthology The Solidarity Struggle: How People of Color Succeed and Fail At Showing Up For Each Other In the Fight For Freedom. Kelly is also a movement photographer whose work is featured in the “Freedom and Resistance” exhibit of the DuSable Museum of African American History.

It has taken me a lifetime to understand that vulnerability is strength, that an open heart takes courage. As a man, this principle goes against everything in how I was raised. I grew up in a small, rural, mill town, a place that if I could describe in short I would say it is old school. Old school in that boys played football, didn’t show their emotion or feelings and kept their pain in check. The be strong and act like a man mentality. This fear induced mentality has limited our growth and spiritual evolution. Yet, you still hear the remnants of this message today. Words that oppress and control women, or fight against feminism and equal wages. Words that divide and create classes, or control. This level of thinking is like the 12 year old bully with…

It has taken me a lifetime to understand that vulnerability is strength, that an open heart takes courage. As a man, this principle goes against everything in how I was raised. I grew up in a small, rural, mill town, a place that if I could describe in short I would say it is old school. Old school in that boys played football, didn’t show their emotion or feelings and kept their pain in check. The be strong and act like a man mentality. This fear induced mentality has limited our growth and spiritual evolution. Yet, you still hear the remnants of this message today. Words that oppress and control women, or fight against feminism and equal wages. Words that divide and create classes, or control. This level of thinking is like the 12 year old bully with…